- Home

- Harry Lembeck

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt Read online

Published 2015 by Prometheus Books

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt: How One Senator Defied the President on Brownsville and Shook American Politics. Copyright © 2015 by Harry Lembeck. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

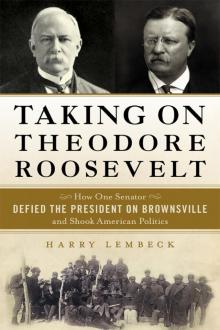

Cover images of Theodore Roosevelt and the Buffalo Soldiers from the Library of Congress; cover image of Joseph Foraker from the Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Burial of General Rosecrans, Arlington National Cemetery, May 17, 1902 (Cincinnati: Robert Clark, 1903), p. 37.

Cover design by Nicole Sommer-Lecht

The Internet addresses listed in the text were accurate at the time of publication. The inclusion of a website does not indicate an endorsement by the author(s) or by Prometheus Books, and Prometheus Books does not guarantee the accuracy of the information presented at these sites.

Prometheus Books recognizes the following registered trademarks mentioned within the text: Springfield Armory®, Tabasco®, Mauser®, Winchester®.

Inquiries should be addressed to

Prometheus Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228

VOICE: 716–691–0133

FAX: 716–691–0137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

19 18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Lembeck, Harry, 1944-

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt : how one senator defied the president on Brownsville and shook American politics / by Harry Lembeck.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61614-954-3 (hardback) — ISBN 978-1-61614-955-0 (ebook)

1. Foraker, Joseph Benson, 1846-1917. 2. Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858-1919—Adversaries. 3. United States—Politics and government—1901-1909. 4. African American soldiers—Texas—Brownsville—History—20th century. 5. Riots—Texas--Brownsville—History—20th century. 6. United States. Army. Infantry Regiment, 25th. 7. Legislators—United States—Biography. 8. United States—Race relations. I. Title.

E664.F69L46 2015

973.91'1092—dc23

2014027260

Printed in the United States of America

“What a cleverly managed and malicious fraud the Brownsville business was.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to Roosevelt,

September 21, 1908,

Roosevelt-Lodge Correspondence 2

“Another method of investigating, with more patience and skill, might easily have brought all the facts to light, and resulted in even handed justice.”

“An Unprejudiced Examination into the

Brownsville Affair,” New York Times,

November 25, 1910

Prologue

Chapter One: The Iron of the Wound Enters the Soul Itself

Chapter Two: “They Are Shooting Us Up”

Chapter Three: A Special Request

Chapter Four: On the Ground

Chapter Five: A More Aggressive Attitude

Chapter Six: The Educations of the Rough Rider and the Wizard

Chapter Seven: Roosevelt Does Justice

Chapter Eight: Friends of the Administration

Chapter Nine: These Are My Jewels

Chapter Ten: Two Sets of Affidavits

Chapter Eleven: Between Two Stools

Chapter Twelve: Grim-Visaged War

Chapter Thirteen: Strange Fruit

Chapter Fourteen: A Different Burden of Proof

Chapter Fifteen: Cordial Cooperation

Chapter Sixteen: Most Implicit Faith

Chapter Seventeen: “What Did Happen at that Gridiron Dinner…?”

Chapter Eighteen: First-Class Colored Men

Chapter Nineteen: Greatest Shepherd

Chapter Twenty: The Soldiers’ Patron and Patronage

Chapter Twenty-One: Other Coalitions, Other Fronts

Chapter Twenty-Two: A Face to Grace the White House

Chapter Twenty-Three: Brownsville Ghouls

Chapter Twenty-Four: “Do You Care to Say Anything on the Subject?”

Chapter Twenty-Five: An Act of Treason

Chapter Twenty-Six: Roosevelt Fatigue

Chapter Twenty-Seven: “Not One Particle of Regret”

Epilogue: What Happened Later

Afterword: What If…?

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

“This is the true joy of life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one.”

George Bernard Shaw, “Epistle Dedicatory,”

Man and Superman, 1903

ARRIVING EARLY FOR A meeting at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian and needing to kill a few minutes in its gift shop, at random I leafed through a book of photos of magnificent houses and buildings in Washington, DC, now torn down and forever lost. By chance I opened it to the home of Senator Joseph Foraker of Ohio. Sturdy and solid looking, the house was far more stately than his wife Julia's cheery description of “a big yellow house” and showed qualities her husband no doubt saw in himself—achievement, material success, respectability, and judgment.1 I vaguely recalled Foraker from the so-called Brownsville Incident. President Theodore Roosevelt blamed black soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Brown for shooting up Brownsville, Texas. At the time of the shooting in 1906, the army was rigidly segregated; black soldiers served only with other black soldiers and were commanded by white officers. The Twenty-Fifth Infantry, the accused soldiers’ regiment, was such a unit. After the army discharged the entire unit on Roosevelt's order, Senator Foraker came to their defense.

Considered the blackest mark against Theodore Roosevelt's legacy is his discharge “without honor” of what would come to be called the Black Battalion. More than one hundred years later, almost no one defends what he did. Some Roosevelt admirers soften their criticism by calling it merely an aberration or a blunder. On the other hand, Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington's biographer, pulled no punches when he called it “the grossest single racial injustice of that so-called Progressive Era.”2 At the time, few disagreed with what Roosevelt did. Most believed that some of the soldiers shot up the town and killed one man while wounding another, that other soldiers knew who the shooters were but refused to finger them, and that all of them deserved the punishment President Roosevelt gave them. Blunder, injustice, racist act, aberration, understandable mistake: whatever Brownsville was, that it only singes Theodore Roosevelt's legacy at its edges indicates his otherwise overall greatness.

Senator Foraker, formerly a successful trial lawyer and onetime Cincinnati judge, who saw the discrepancy between accusation and conviction, evidence and proof, said dismissing all for what may have been the acts of only a few was wrong. He took up their cause and worked tirelessly and publicly for them. Foraker understood that President Roosevelt, emulating his hero Abraham Lincoln, had strengthened his office with immense power and would use all of it against him brutally and personally.3 He also had to know that Roosevelt had what Professor Lewis Gould has called the “unlovely aspect” of behaving unfairly with his opponents.4 When Foraker took his stand for the soldiers, Roosevelt had been in the White House for five years and led an active government that, among other things, busted the big-business combines known as trusts and freely acknowledged that America was entitled to act as the world power it ha

d become. Fighting in Cuba, digging the Panama Canal, warning European powers away from the Americas with his own corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, influencing affairs in the faraway Pacific Ocean region by mentoring a peace treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese War (and receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for it), and creating a special relationship with Great Britain that would help win a future World War II, Roosevelt stood second to no one in bringing about what Time magazine publisher Henry R. Luce would call the “American Century.”5

With his intellectual restlessness yoked to a physical energy that was nothing less than astounding, Theodore Roosevelt seemingly was everywhere and knew what went on every day. To accomplish all he wanted for the future he foresaw for his country, and breaking with the more restrained presidencies of his predecessors since Lincoln, he fortified the government with a greatly strengthened chief executive. In what would become an on-again, off-again process by most of his successors for the next hundred years, he expanded its scope, responsibilities, and powers. To justify his actions, he reinterpreted the Constitution his way and proposed bedrock changes to the federal system. Washington, DC, could not contain him. He often traveled away from the capital and thought nothing of going as far as California and the western states for extended periods. He even went to Panama in 1906 to see his canal under construction and to congratulate himself for bringing it about and showing the world what his America could do.

He changed the Executive Mansion itself. Almost immediately after his wife, Edith, unpacked their bags, he changed its name to the White House. Much better, he thought. It was natural, free from pretension, so purely American. Just as Roosevelt saw himself. It told the world that in a powerful America, even its leader lives in a simple, white house. But this was nonsense. As the presidential office grew, the office where he did business, and even the White House itself, seemed too small. Roosevelt expanded it by adding what is now called the West Wing, today the location of the Oval Office. The White House facade, reflecting the calm and restrained tastes of an earlier period, was an illusion screening a complexity that could not begin to describe the man Theodore Roosevelt was. Roosevelt found positively distasteful the way Senator Foraker saw America and how it should be governed. Where Roosevelt would increase government's sprawl, Foraker preferred it stay limited. Roosevelt was suspicious of big business; Foraker the lawyer represented it in court. When Roosevelt sought to apply the government's strength in court to restrain runaway companies, Foraker worked in Congress to protect them.

History has not yet been able to show Roosevelt was wrong in what he thought happened, even if it adjudges him wrong in what he did about it. Just who the shooters were is an enigma still unanswered more than a century later. Within the mystery is the tandem of Roosevelt and Foraker and their battle that continued beyond Foraker's days in the Senate and Roosevelt's time in the White House.

The Brownsville Incident was a snapshot of race in America in the early twentieth century and a pivot point in the struggle for equal treatment for black Americans. Voting rights were sharply curtailed. Jim Crow laws became a way of life in the South, segregating everything from streetcars to Pullman trains, toilets to restaurants, hotel accommodations to schools.6 Black leaders were unsure of just how to deal with this. The greatest Negro leader of the day, Booker T. Washington, counseled accommodation and patience. So great was his influence, so respected was he for his accomplishments and position, for some time thereafter there was no effective counter-message from other black leaders. By 1906 and Brownsville, this would be changing, and others, notably W. E. B. Du Bois, were pushing hard for a more aggressive course of action. With his easy eloquence and forceful presence, Du Bois used Brownsville to chip away at Washington's leadership and redirect the movement for equality. The Brownsville Incident and Theodore Roosevelt's actions after it would be pulled into the collision between these two men. There were men, both black and white, who agreed with Foraker and stood with him in common cause. Others stayed with Roosevelt. Still others recognized there was justice in Senator Foraker's poking about but hung back from endorsing his quixotic pursuit. One was Booker T. Washington, who saw Roosevelt as a source of his own power and influence.

Roosevelt's personal magnetism beggars description, and those who attempt to do so sketch a phenomenon of nature. “He was his own limelight, and could not help it: a creature charged with such a voltage as his, became the central presence at once, whether he stepped on a platform or entered a room—and in a room the other presences were likely to feel crowded, and sometimes displaced.”7 Roosevelt's friend William Hard captured his extraordinary qualities when he said, “He was the prism through which the light of day took on more colors than could be seen in anybody else's company.”8

A century later, Theodore Roosevelt is securely settled in as one of America's great presidents. In a 2010 poll ranking presidents, he was ranked overall number two, ahead even of Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson.9 On twenty-first-century problems ranging from immigration to war to conservation, his views are cited by one side or the other or both. Bigger than any man of his era, Theodore Roosevelt was considered as great as the country he led. When he left the White House in 1909 he was the most famous man in the world. Joseph Foraker is forgotten, and the Black Battalion is barely remembered.

“To him, principle and right were more important than political preferment. He should have our eternal gratitude. I wonder if again we will find another such friend and supporter.”

William Sanders Scarborough,

former slave and president of Wilberforce University,

speaking about Joseph Foraker

“THE OLD MAN HAS fought for the reinstatement of our soldiers since 1906 and I do hope that his stand for justice will be appreciated by the black people of the country,” wrote Ralph Tyler in 1909 to George Myers, an influential political leader in Cleveland's black community. Myers had been Tyler's mentor and at one time a close friend. “The old man” he referred to was Senator Joseph Benson Foraker, Republican of Ohio. “On the 6th of March,” Tyler went on, “the colored citizens of Washington are going to present him with a loving cup at the Metropolitan Church and from the effort that is being made I am sure he will be given a great ovation.”1

In his own mind, Myers must have questioned just how genuinely Tyler associated himself with Foraker and the effort to honor him. After the Brownsville shootings but before the incident became divisive, Tyler ingratiated himself to Foraker. On September 15, 1906, he complimented the senator on a “splendid speech” at the Ohio Republican Convention in Dayton. Tyler gushed, “You came, you saw, you conquered, as you deserved to do.”2

Twelve days later Tyler ended another letter by fawning, “It is only my great admiration for you…and my desire to see you victorious in everything that prompted my writing…. You know, Senator, I am a REAL Foraker man, and am always with you and for you, whether in defeat or in victory.”3 Two months later, when Foraker took up Brownsville in the Senate, Tyler told him he was “our champion, and I thank you from the bottom of my heart.”4

But shortly thereafter, when defending Roosevelt became the touchstone for loyalty to him and, even more important, a qualification for appointment to a federal job desired by Tyler, he jumped to Roosevelt's side and worked to persuade people to give Roosevelt a pass for what he had done. When Roosevelt made him fourth auditor of the navy, Myers, who by now had wiped his hands of Theodore Roosevelt over Brownsville, warned him not to undermine Foraker with Negro voters. “There is no doubt in my mind of Foraker's ultimate victory…[and] I am writing to you this fully, to demonstrate the futility of the President to corner or stop the stampede of the colored voters of Ohio by your appointment.”5

By March 1909 and Roosevelt's last days in the White House, Tyler was back on Foraker's side and applauding the efforts of the man who had been the most active and visible man working to reverse President Roosevelt's order to discharge “without honor” 167 soldiers of the army's Twenty-Fifth Infantry

, now being called the “Black Battalion,” for their alleged involvement in a deadly shooting in Brownsville, Texas. He insisted the soldiers had been denied justice, publicly accused Roosevelt of punishing innocent men, compelled the Senate to investigate Roosevelt's action, and doggedly worked to reverse their discharges for as long as he remained in the Senate. In one of his final appearances in the Senate, barely two months before Ralph Tyler's letter to Myers, he pleaded to his colleagues and the nation, “They ask no favors because they are negroes, but only for justice, because they are men.”6 An enraged Roosevelt was forced to defend himself. Already fed up with Foraker for past differences of opinion, Roosevelt now made him an archenemy.

There was no doubt among Negroes that Foraker had worked his heart out. In the Senate committee hearings on Brownsville, Foraker demonstrated why he was a very successful lawyer: attention to detail, thorough preparation, skillful argument, and forceful presence. He made hash of President Roosevelt's arguments defending the soldiers’ dismissals. Even many whites believed Foraker was convincing and had shown Roosevelt to be wrong. Only a month into the committee hearings the Washington Times would write, “There is a strong feeling among many who have followed the testimony…that it already has been proved very doubtful if the soldiers did do it.”7 Black Americans, to whom Roosevelt had been thought a friend and an ally in their slow, painfully frustrating, and always disappointing push for the rights of American citizenship, now questioned whether Roosevelt could be trusted.

WHEN HE WAS OHIO governor in the 1880s, Joseph Foraker was known as “Fire Alarm Foraker” for his ringing, white-hot public speaking. On the stump he often used his blowtorch style and language to remind people of the rebellion of the Confederacy and the slavery the South sought to hold onto and was willing to split the nation to keep. Rhetoric like his was called “waving the bloody shirt,” and Joseph Foraker employed it often to remind people what it had cost to preserve the Union. He believed it showed the voters he had “fire and courage.”8 He was not shy about using this for simple political advantage, coupling an “unwavering justification of the Republican stand during and after the Civil War” with a flair for partisan argument.9

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt

Taking on Theodore Roosevelt